“Atlanta is the world’s most profitable and powerful airline hub,” my friend and former colleague

frequently tells me.And Shabat would know. He co-authored the book on Delta Air Lines’ post-9/11 rise, Glory Lost and Found, as well as co-founder and an analyst at Skift’s Airline Weekly. And anyone familiar with Delta’s business knows its hub at Hartsfield-Jackson Atlanta International Airport is critical to its success.

Atlanta is the busiest airport in the world by a wide margin; it saw nearly 105 million annual passengers in 2023 compared to runner up Dubai International Airport’s nearly 87 million, according to the Airport Council International’s annual ranking. And it does that on about two-thirds of the land of Dubai’s airport, and even less when compared to modern mega airports like Denver, Doha, or Shanghai Pudong.

And it handles all those passengers at very low costs. The average cost per enplaned — or boarded — passenger in fiscal 2023 (the year ending that July) was just $2.23, according to the airport. For comparison, the metric was $11.56 and about $11 at major U.S. hubs Dallas-Fort Worth and Denver, respectively.

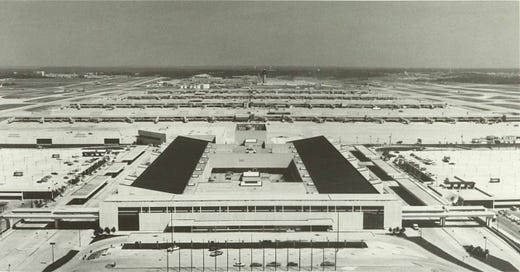

What is Atlanta’s secret sauce? The design of its 1980 midfield terminal by Stevens & Wilkinson, and Smith, Hinchman & Grylls (now SmithGroup).

If you are one of the 105 million people that pass through the crowded, low-ceilinged corridors of the Atlanta airport today, you could be forgiven for not realizing that it was a seminal design. The brutalist terminal, the underground Plane Train and its parallel concrete corridor — the exception being the phenomenal forest-like “Flight Paths” between concourses A and B — and the uninspired linear concourses create a utilitarian aesthetic.

“Hartsfield raised the brutalist aesthetic to a new level,” wrote Alastair Gordon in Naked Airport. “The Midfield Complex was a 2.2-million-square-foot warren. Its megalithic concrete slabs were relived only by the occasional monitor skylight or venting duct. Dallas-Fort Worth seemed intimate in comparison.”

But Hartsfield-Jackson’s midfield terminal is important. It was the first major airport designed as hub where a majority of travelers connected between flights rather than came from or went to Atlanta. Many of its peers, particularly HOK’s Dallas-Fort Worth (opened 1974), adopted the prevailing airport design paradigm of the time that prioritized short distances from the curb to the gate.

Atlanta’s concourses separated by 1,000ft taxiways and connected by an underground train (and walkway) to a single terminal building — the second international terminal designed by Gresham Smith opened in 2012 — has became the basic blueprint of large airport design in the four decades since it opened.

Chicago O’Hare Terminal 1 by Helmut Jahn (opened 1987) and the underway O’Hare 21 plan; Denver by Fentress Architects (opened 1995); Detroit McNamara Terminal by SmithGroup (opened 2002); Munich’s Terminal 2 by Koch + Partner (opened 2003); and London Heathrow Terminal 5 by Richard Rogers Partnership (opened 2008) and Terminal 2 by Luis Vidal + Architects (opened 2014) are just a slice of the airports that have followed in Atlanta’s design footsteps.

How the team led by Stevens & Wilkinson got to the midfield layout was far from linear. It took twists and turns, and drew from the major U.S. airport projects of the 1970s.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Airport Architecture to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.